Taste the State of South Carolina With Kevin Mitchell & David Shields

Discovering the Palmetto State's signature foods, recipes & stories

Posted October 12, 2021

10-12 2021

Updated October 12, 2021

In these days of regional cross-fertilization, the dishes that were once unique to the Carolinas have increasingly been lumped together with specialties from far afield into a sort of homogenous pan-Southern cuisine. You can now find shrimp and grits on fine dining menus in Nashville and Memphis, and pimento cheese has become a sort of all-purpose condiment, slathered on everything from burgers to fried green tomatoes.

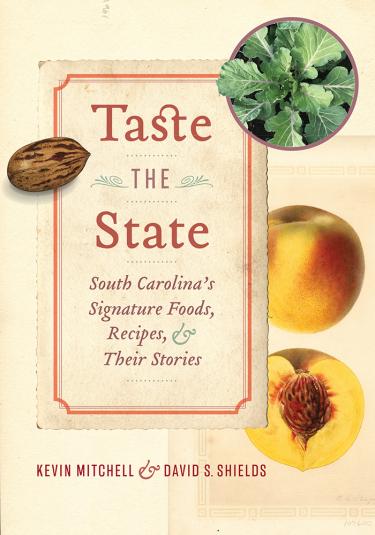

Kevin Mitchell and David S. Shields hope to cut through all the murkiness and refocus diners’ attention on the dishes and ingredients that have long made South Carolina cuisine unique. Today (October 12) is the official publication date of their new book Taste the State: South Carolina’s Signature Foods, Recipes & Their Stories from the University of South Carolina Press.

Mitchell holds degrees from the Culinary Institute of America and a master’s in southern studies from the University of Mississippi, and he is the first African American chef instructor to teach at the Culinary Institute of Charleston. Shields is a professor of English at the University of South Carolina, the chair of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, and the author of several other books on Southern culinary history.

Instead of “a greatest southern hits collection,” Mitchell and Shields aimed to gather ingredients and recipes with genuine South Carolina roots. The result is a volume billed as “a guide for those who want to know South Carolina food more deeply.” It presents 82 of the state’s most distinctive dishes and ingredients.

Some will be comfortingly familiar to almost all Carolina diners, like peaches, oysters, and Duke’s mayonnaise. Others may be unknown to all but the most adventurous eaters, like mullet and mullet row, Yaupon tea, and cooter soup. The book also includes plenty of recipes, both historical ones and more modern interpretations, like Chef Mitchell’s takes on Hopping John, she-crab soup, and tomato gravy.

We wanted to give a little flavor of the lesser known delicacies to be found in Mitchell’s and Shields’s book, so we selected the entry on liver pudding—an old South Carolina breakfast specialty. If you’ve not tried fried liver pudding before, just duck into any of the thirteen Lizard’s Thicket restaurants in and around Columbia. For just $7.49 you can get a liver pudding plate with eggs, toast or biscuits, and your choice of grits, hash browns, country skillet apples or sliced tomatoes. (Get the grits.)

Liver Pudding

Excerpted from Taste the State: South Carolina’s Signature Foods, Recipes & Their Stories by Kevin Mitchell and David S. Shields. Reprinted with permission.

Originally a seasonal food appearing in butcher stalls in December, liver pudding had two styles in South Carolina: one incorporating corn meal as its grain binder, the other rice. Made from hog liver and lights (lungs), stomach and lips, sometime the head, cooked long and chopped fine, it made use of one of the two most popular grains in the region cooked to a porridge when mixed with the meat, then seasoned. The mixture was either put into casings for sausages or poured into molds to cool into bricks. Both forms appeared on the Winter breakfast table prior to World War II. Nowadays it can appear at any meal—even with fried slices appearing as the focus of sandwiches at lunch.

Traditionally liver pudding was home made as the culmination of the cold weather slaughter of hogs. As a do-it-yourself preparation, makers introduced a fair amount of variation in the formula. Liver pudding without liver—double charges of sage and black pepper—garlic.

From the Civil War onwards complaints arose when another’s pudding tasted different from one’s own. Against the DIY chaos certain butchers defined a norm of flavor and texture. Butcher Brill in stall eight at the Columbia market shaped the public sense of what the corn meal version of liver pudding should be immediately after the Civil War. Mrs. Stoudemeyer of Newberry and J. A. Darwin of Yorkville specialized in the German seasoning of Liver Pudding. (Pan parching the corn meal brown before adding, sage, thyme, black pepper, mace, and salt.) Darwin moved to Charleston, secured the services of butcher Charles Boppe, and at a stall in the market sold liver pudding using a German seasoning and a rice binder. This would become the standard formula for Lowcountry liver pudding. He announced “Liver pudding is one of the delicacies that the people of Charleston have been missing for a long time, for the reason that it has been a long time since there has been a man in Charleston who could properly prepare the ingredients and give it a proper flavor. My Mr. Boppe thoroughly understands the preparation of the ingredients and the seasoning for Liver Pudding and is producing an article that is delicious.”

Boppe’s style of liver pudding employed rice as a binder, sage, thyme, pepper and onions. It was housed in sausage casings and was equally savory cooked hot or cooked and sliced cold. But it was not unusual for liver pudding to be sold in rectangular loaves like scrapple. Palmetto Farm Brand Liver Pudding, a mainstay of the third quarter of the twentieth century sold it in this form, double branding it as liver mush/liver pudding. Liver mush is the preferred name for liver pudding in western North Carolina. No hog hearts were used in their formula. Most of the commercial brands available hereabouts deviate from the classic recipe. Neese’s from North Carolina adds wheat flour to the corn meal. Four Oaks farm from Lexington has the classic rice, onions and pig parts, but no liver.